Several of the tracks on Burnin’ were re-recordings of songs that had been released before. Wailer found the touring onerous and once the band had returned to Jamaica, he was reluctant to leave again.Īlthough a “new” act in Britain and America, the Wailers had been singing and recording together since 1963, and could boast a plentiful catalogue of songs which were largely unknown outside Jamaica. Dissatisfactions among the founders built up during a schedule which took them to America for the first time.

As with Catch A Fire, his songs accounted for the great majority of tracks, which may have been why Burnin’ was the last album before both Tosh and Wailer left the group. With the encouragement of Blackwell, Marley emerged once again as the primary singing and songwriting voice of the Wailers on Burnin’. The song would be re-recorded on subsequent solo albums by both Tosh and Wailer and would remain a key number in Marley’s repertoire to the end of his career indeed it would be the last song he ever performed on stage (in Pittsburgh in September 1980). “Preacherman don’t tell me heaven is under earth,” Marley sang with evident disdain. Interestingly, the lyric specifically criticised religious teachers for creating a smokescreen with promises of a paradise to come, thereby distracting people from claiming their rights as human beings here on this world. Marley and Tosh are said to have co-written the song while touring Haiti, where they encountered extremes of poverty that were the equal of anything in Jamaica. The album’s opening track “Get Up, Stand Up” became an enduring anthem of people power, adopted by civil rights activists the world over. This harsh, edgy yet spiritually rich environment provided an immensely powerful backdrop to the songwriting of Marley, Tosh and, Wailer, and never more so than on Burnin’. Large swathes of the city had become urban ghettoes where the key players in a rudely vibrant music scene rubbed shoulders both with the victims of abject poverty and the trigger-happy “posses” (gangs) of loosely-organised criminals. The rapid post-war influx of people from the land into Kingston, had triggered an era of haphazard growth and wildly uneven wealth distribution in and around the capital. For most of its history, Jamaica had been a rural economy. These two songs alone marked out Burnin’ as an album that gave serious voice to some heavy social and cultural concerns. It would be another year before Eric Clapton took his version of the song to No.1 in the US (No.9 in the UK), a game-changing hit which would transform the worldwide perception and fortunes of reggae music at a stroke. “If I am guilty I will pay,” Marley sang, but the story left little room for doubt that this was a righteous killing provoked by a history of grievous mistreatment by the lawman in question. Meanwhile, the album’s most celebrated song, “I Shot The Sheriff” was a precursor of the murderous street stories that would later come to define American gangsta rap.

#BOB MARLEY BURNIN FULL#

The melody was mournful, the tone full of anger and regret as Marley pondered his people’s predicament: “All that we got, it seems we have lost.” Powered by Aston “Family Man” Barrett’s supremely melodic bass line and brother Carlton Barrett’s one-drop drum beat, the song had a groove that hovered somewhere between a funeral march and an all-night shebeen. The album’s almost-title track “Burnin’ And Lootin'” promised a full-scale riot. Burnin’ upped the ante in all departments.

Island Records supremo Chris Blackwell, who had begun his career selling records by Jamaican acts from the boot of his car to the expatriate community in Britain, knew a thing or two about this particular market and now scented something spectacular in the air.Ĭatch A Fire had not only introduced the sinuous rhythmic charms of reggae music, it had also alerted the world to the cry for justice of a poor and historically dispossessed people.

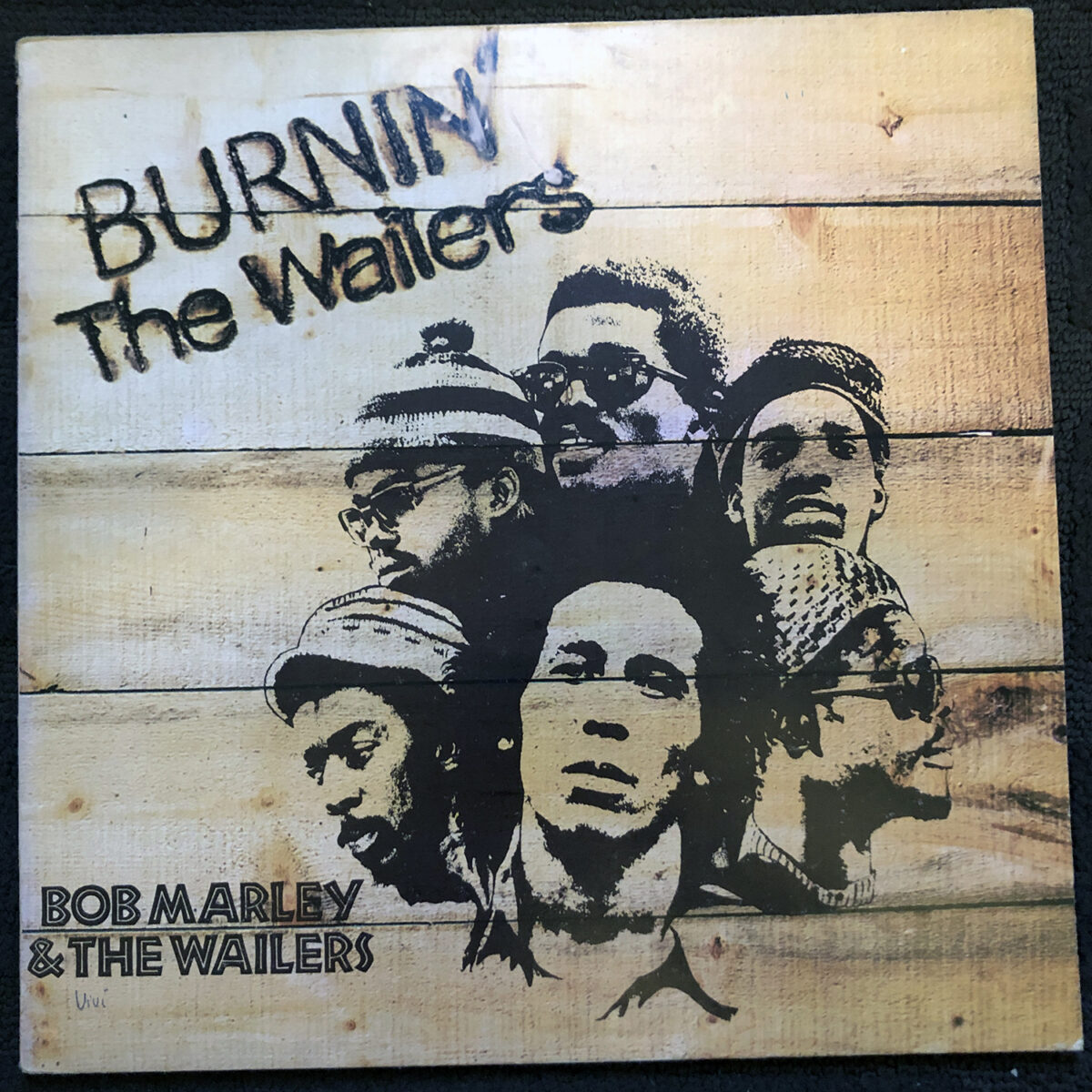

Still billed only as the Wailers, and still led by the three-man vocal front line of Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, the band was now moving through the gears with an increasing sense of mission.Īlthough Catch A Fire had not been a hit, the response to it among tastemakers and early adopters had been overwhelming. Less than six months after the Wailers released their first international album, Catch A Fire on 4 May, the conflagration continued with the release of Burnin’ on 19 October.

Things moved fast in the music business of 1973.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)